Two companies with completely different products—one is designing three-wheel solar cars, the other builds tiny houses that unfold like tents—exemplify this growing segment of the market, known as crowdfunding.

Tens of thousands of small investors have poured $170 million into Aptera Motors and Boxabl, but have little to show for it.

The companies have sometimes misled investors as they burn through tens of millions of dollars, struggle to generate sales, and continue to seek more money, according to people close to the companies, internal documents and whistleblower complaints filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Aptera has been telling investors for three years that it would soon deliver its first solar-powered car but still hasn’t shipped any. Tiny-house maker Boxabl says its wait list exceeds 175,000 customers, but it has sold only six units this year, according to its most recent disclosures.

The SEC approved the exemption nearly a decade ago, as part of an effort to make it easier for smaller companies to raise capital. Known as Regulation A, the technique allows businesses to annually raise as much as $75 million while complying with lighter-touch rules than a traditional initial public offering. These companies have raised billions of dollars from hundreds of thousands of Americans with little oversight.

Aptera and Boxabl have both relied on catchy social-media campaigns that hype their progress creating game-changing technologies. Crowdfunding platforms—such as StartEngine and Republic—match the fledgling firms with novice investors who can behave more like fans than shrewd financiers looking for a solid return on their investment.

Shares bought through crowdfunding platforms aren’t listed on an exchange and don’t freely trade. Investors are locked into their stake unless the company arranges a sale or conducts an IPO.

No cars in sight

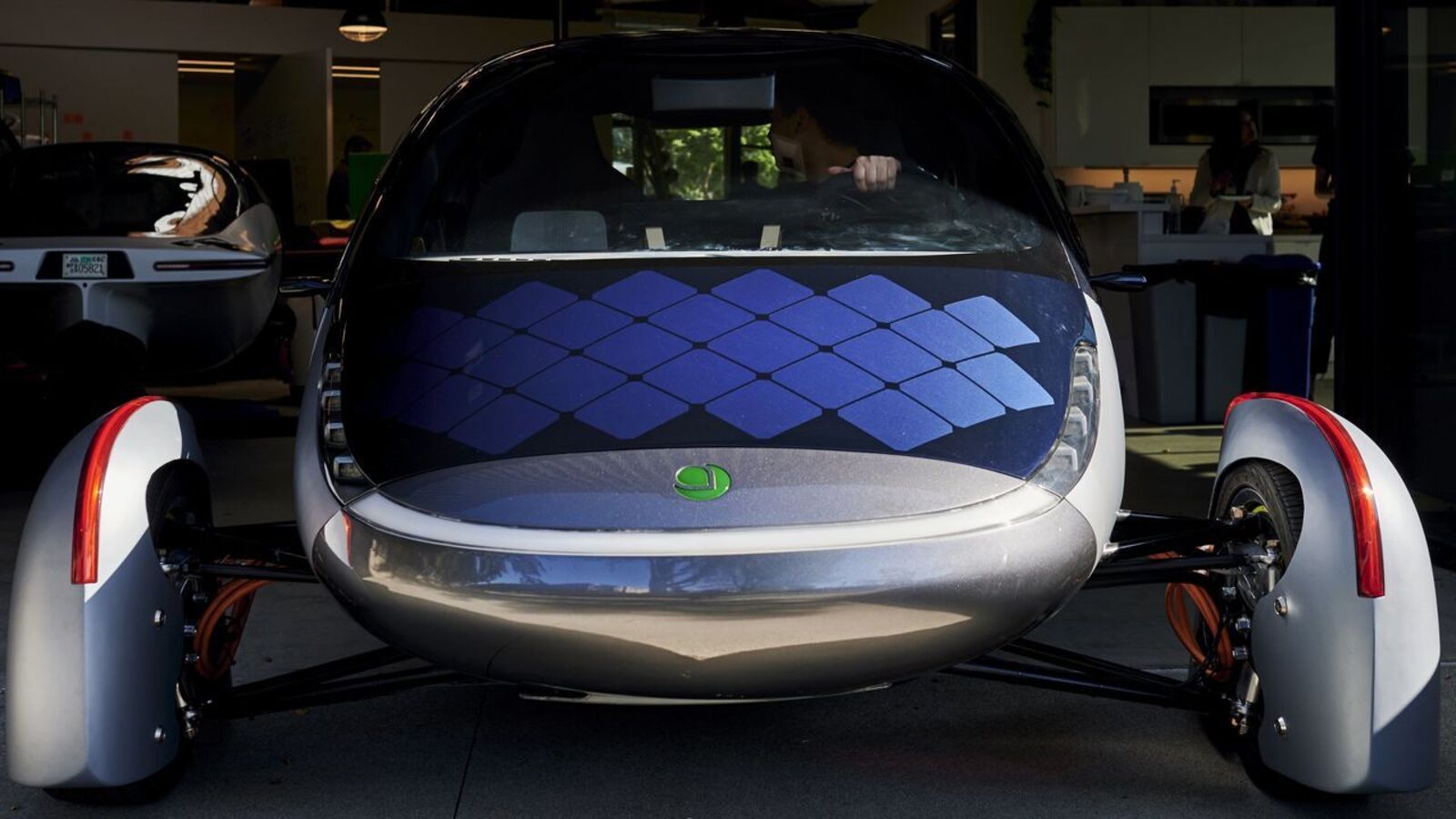

Aptera has raised more than $120 million from 17,000 investors since 2021, building a dedicated fan base through videos posted on YouTube and Instagram that tout a three-wheel electric vehicle that it says will eventually have a 1,000-mile range. Tesla’s electric vehicles, by contrast, have a range of between 300 and 350 miles before they need to be recharged.

Aptera, based near San Diego, went bust in 2011 after it ran out of money and failed to qualify for federal loan financing, but crowdfunding gave the company a second life. Its funding haul includes $100 million through Regulation A. Company officials internally have referred to their social-media campaign as “clickbait” because each new video typically brings a flood of new investments.

Though Aptera has pushed back its production date several times, many of its small investors express devotion to the concept.

“Every time I see another video about Aptera the farther I fall in love with this car,” one person wrote on a recent YouTube video. “Aptera really embodies the statement, ‘Do it right, or don’t do it at all.’”

Crowdfunding investors often accept less transparency and fewer rights than professional investors who negotiate stakes in private companies. And they are wagering on companies with little to no record of success.

About 85% of companies that sought capital under the SEC’s Regulation A exemption had either zero profits or negative net income, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis of commission data since 2016, when the financing model was first made available.

“I advise approaching these unproven investments with the same caution as responding to a flashing check-engine light—if you choose to proceed, do so with extreme caution,” said David Krause, a finance professor at Marquette University who has closely studied this market.

Aptera told investors in a July 2023 video that it had validated the aerodynamic design of its three-wheel car at a wind tunnel in Italy. It presented the results as proof of its progress.

But the trip to the wind tunnel was mostly a chance to crank out another advertising video, according to people familiar with the trip.

Aptera spent only a few hours at the tunnel, which wasn’t designed to test three-wheel vehicles such as the Aptera, which is classified as a motorcycle, the people said.

In an interview, Co-Chief Executive Chris Anthony said the company got an invitation on short notice to use the wind tunnel and decided to use the opportunity as best it could.

“We didn’t have time to coordinate with them or talk about, you know, the special needs of a three-wheel vehicle,” Anthony said. “And certainly we didn’t write them a big check, so they didn’t have a lot of incentive to say, ‘Hey, let’s customize the wind tunnel for these guys.’”

“But we got pretty pictures,” he said.

Anthony said in an October video that “the vehicle is ostensibly done,” even though several systems had yet to be built at the time, and the frame was undergoing a major redesign while some parts didn’t have suppliers, according to records viewed by the Journal.

Anthony told the Journal that his description of Aptera’s progress was accurate. Aptera was still sourcing and improving some components and features but “in October we could have built that vehicle,” he said.

Its annual regulatory filings show Aptera burned through about $25 million last year and had $17 million in cash on hand at the end of 2023. The company disclosed a “going concern” warning, which alerts investors that it probably can’t remain in business without raising additional capital.

In a new bid to attract more capital, Aptera said in April that investors who gave at least $2,000 would receive $1,000 off the price of a vehicle when they are delivered. Investors who contribute at least $27,000 would get the first vehicles that are delivered in the United Arab Emirates, where Aptera is trying to raise money and find customers. In a recent video, the company showed an Aptera doing “tons of laps” on a racetrack in Abu Dhabi.

Aptera has lost both of its outside board members in the past year, with the most recent director resigning on May 3.

Three weeks ago, after being contacted by the Journal for this article, Aptera announced it would stop using Regulation A by the end of June. It said it hired a San Francisco-based investment bank, US Capital Global, to help it raise money from wealthy investors.

On May 30, it notified the SEC about its plans to raise $5 million in a smaller crowdfunded round.

Tiny homes that few people want

Las Vegas-based Boxabl has raised $150 million by telling investors that it will automate home-building by cranking out factory-built tiny houses in 15 minutes. The company’s father-and-son management team, Chief Executive Paolo Tiramani and Chief Marketing Officer Galiano Tiramani, say their mission is to churn out 360-square-foot homes that could one day be sold on Amazon.

Four years in, Boxabl has delivered only 223 of the dwellings known as Casitas—most of them through one order to the U.S. government’s naval station in Guantanamo Bay.

The SEC is investigating the company over its disclosures to investors. Its auditor resigned last month after identifying a material weakness in Boxabl’s systems for valuing stock-based compensation and accurately disclosing financial information to investors. Boxabl said it believes the auditor’s concerns were resolved.

Boxabl initially agreed to answer questions for this article but never provided responses.

The company has sought to tie itself to the master of self-promotion on social media: Elon Musk, who confirmed on a 2022 podcast that he has a Boxabl unit in South Texas. Boxabl has opened its doors to YouTube personalities and influencers who visit its Las Vegas factory to make videos with titles like “Inside Elon Musk’s Famous $50,000 Tiny Home.”

The company is storing 325 Casitas valued at about $15.4 million, according to SEC filings. In some states, it still needs permits from regulators to sell the units. It recently started offering them to residents of recreational-vehicle parks.

Wearing a snapback hat and a rolled-up mechanic’s shirt that shows off muscular arms, Paolo Tiramani said on a recent YouTube video that his company’s struggles are due to regulation that is “next level nuts…and it’s mostly the result of unintended do-gooding.”

Eliana Sheriff, a YouTube content creator who made that video and several others focused on Boxabl, said she won’t do more “until they can prove there is something worth covering other than buying a factory a block down the road with nothing in it.”

The potential for quickly producing profitable units was a big selling point to early investors. When Boxabl raised money through crowdfunding for the first time in 2020, it told investors that it would sell units at $50,000 and earn a net profit margin of $20,000, or 40%, on each Casita.

Boxabl lost $40 million last year, according to SEC filings. People close to the company say it expanded too fast, leasing three large factories in Las Vegas before it knew if it could sell units across the country.

Though Boxabl has touted a lengthy wait list of customers, most haven’t put down a deposit. Fewer than 10,300 paid a deposit of between $100 and $49,500, according to records viewed by the Journal.

Despite Boxabl bleeding cash, Paolo and Galiano Tiramani were both awarded bonuses of $297,500 last year, according to SEC filings, or 50% of their annual salaries of $595,000. Their salaries, high for a startup where founders are typically compensated mostly in stock or options, have stirred concerns inside their company.

“This does look like a money grab,” Jennifer Katz, the company’s former vice president of strategic investments, wrote in a text message to another ex-employee that was viewed by the Journal. Katz declined to comment.

Boxabl’s Regulation A share sale generated about $75 million. But Boxabl got only about $65 million of that because Galiano and Paolo Tiramani sold $10 million of their own shares late in the offering process. The company disclosed a valuation of $3.4 billion that year.

Most investors paid 80 cents a share in the offering. But Boxabl offered a limited number at just one penny. The biggest buyer at that discount was Galiano Tiramani’s wife, Shawna Maslak, who acquired 1.9 million shares for $27,000, according to records viewed by the Journal. Boxabl didn’t disclose in its SEC filings that Maslak was eligible to buy at the lowest price.

The company is seeking SEC approval to raise another $75 million through Regulation A. It is offering large discounts on the 80-cent share price, which small investors pay, to entice wealthier investors to contribute $1 billion to build an even larger “Boxzilla” factory.

Boxabl suffered another setback when a Canadian vendor, Brave Control Solutions, that was supposed to deliver $15 million in automation equipment went out of business. Boxabl sued Brave in April, claiming it paid $8 million but never received any equipment.

“It’s sent me down a rabbit hole to find a better way. I think I have,” Galiano Tiramani told investors in a post on Facebook after Brave folded.

“As soon as I’m allowed to I will share some info on the new path I have planned,” he said.

Kirsten Grind and Dan Gallagher contributed to this article.

Source: bing.com