When particle physicist Andy Yen launched the privacy-focused email service Proton Mail as an ambitious crowdfunding campaign in 2014, the ultimate goal was to make it easier for people to be private online. Now, more than a decade on, his Switzerland-based company, Proton, is in the process of taking one of its biggest potential steps to reduce Google’s online dominance.

Today, Proton is launching the ability to create, edit, and collaborate on end-to-end encrypted documents within its online file storage systems. This means that only the creator of a document, and anyone they have shared it with, can view the contents of the file. Nobody else, including Proton, can see what has been written in the documents, according to the company.

The move to add encrypted documents to Proton is a shot at the data-hungry approaches of Google and Microsoft, which both host individual and business cloud services but don’t encrypt files and can also collect vast amounts of data about people. It also makes Proton one of only a handful of businesses providing encrypted documents and editing online.

“One thing that we’ve heard a lot from both businesses and also consumers is that they need a document product, because Google Docs is the reason they stay on Google,” Proton founder and CEO Yen tells WIRED. “It will look and feel a bit like Google Docs, because in fact, it’s supposed to be easy for people to adopt. The biggest barrier to privacy has always been user experience.”

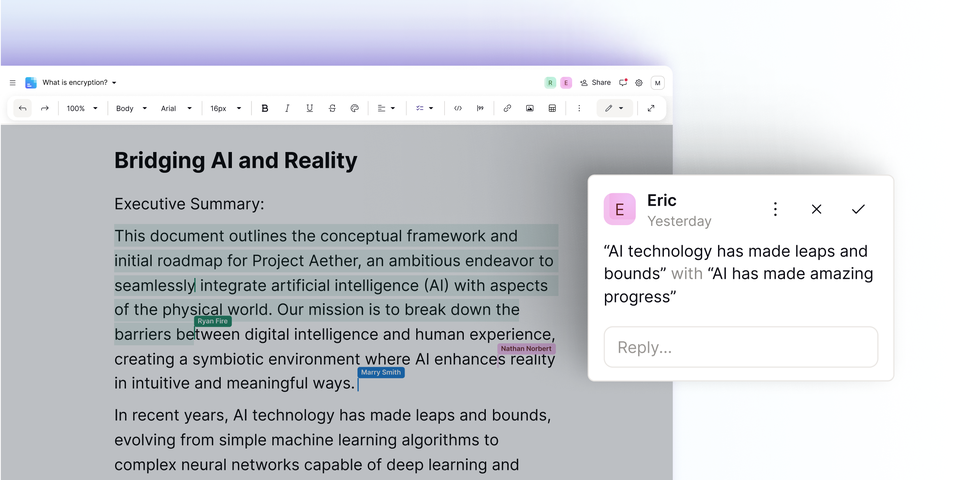

Documents in Proton Drive, which will start rolling out to people today, does look like Google Docs. In screenshots shared by Proton, it appears to be a clean document editor, with many of the standard options you would expect: font and text changes, formatting, adding links, images, and more. The document editor is initially only available on the web and not in app form.

Yen says Proton has been internally using the system for the last month and is now ready to roll it out to consumers. “I feel it is relatively polished,” Yen says. To compete with other online document editors, he says, the team also built in collaboration functionality from the beginning. This includes real-time editing by multiple people, commenting, and showing when someone else is viewing the document.

In April, Proton acquired encrypted note-taking app Standard Notes, which is a separate product from Docs. “It’s actually not ‘take Standard Notes and stick it into Proton,’” Yen says, adding that the encryption architecture of the two were different, and Proton Docs is “more or less a ground-up, clean build in Proton’s ecosystem on our software stack.” (WIRED was unable to test the Docs before it was launched).

The big difference Proton is adding when compared to Google Docs is the encryption—something that is challenging to do at scale and also harder when a document has multiple people editing it at the same time. Yen says it’s not just the contents of documents that are being encrypted, so are other elements like keystrokes, mouse movements, and file names and paths.

The company, which last month announced it is moving toward a nonprofit status, uses open source encryption, and Yen says building the Docs system required encryption key exchange and synchronization to happen across multiple users. Part of this was possible, Yen says, because last year the company added version history for documents stored in its Drive system, which the Docs are built on top of.

There are relatively few—if any—major end-to-end encrypted document editors online. Other existing services, which WIRED has not tried, include CryptPad and various note-taking or notepad-style apps. There are also apps that encrypt files locally on your machine, such as Cryptee and Anytype.

Recently, Proton has been moving quickly to launch new encrypted products—adding cloud storage, a VPN, a password manager, and calendar alongside its original ProtonMail email service. The company has also faced scrutiny over some information it has provided to law enforcement, such as recovery emails that have been added to accounts. It changed some of its policies in 2021 after being ordered to collect some user metadata. While the company is based outside of the US and EU, it still responds to thousands of Swiss law enforcement requests.

Ultimately, Yen says, the company is trying to offer as many private alternatives to Big Tech services, particularly Google, as it can. “Everything Google’s got, we’ve got to build as well. That’s the road map. But the challenge, of course, is the order in which you do it,” Yen says. “In some sense, taking privacy to a more mainstream audience also requires going further afield, trying different things, and being a bit more adventurous in the things that we build and things that we launch.”